Warning: Use of undefined constant setting - assumed 'setting' (this will throw an Error in a future version of PHP) in

/home/engnet/www/www/wp-content/plugins/cite/cite.php on line

105

Reading Time: 8 minutes

First Published on Evidence Based EFL, Monday 9th February 2015

Richard Pinner

Introduction

At the end of 2014, I was lucky enough to be invited on to the TEFLology Podcast to discuss authenticity.

Listen to it here

The reason I was asked is that I am doing a PhD in which I am (attempting) to look at the connection between authenticity and motivation. I am also currently working on a book about authenticity which will be available next year (all being well).

Authenticity in language teaching is a thorny issue, and especially in English language teaching because of the nature of English’s use worldwide as an international language, with many diverse varieties. What do you understand by the term authenticity? For most language teachers, the word authentic is part of our daily vocabulary. It is stamped onto the backs of textbooks, it is mentioned when describing a particularly motivating task, and it is often used alongside other words like motivation and interest. So, just what do we talk about when we talk about authenticity?

Shadow-boxing with the definition

In his now famous article, Michael Breen (1985) identified that language teachers are ‘continually concerned with four types of authenticity’, which he summarise as:

- Authenticity of the texts which we may use as input data for our learners.

- Authenticity of the learners’ own interpretations of such texts.

- Authenticity of tasks conducive to language learning.

- Authenticity of the actual social situation of the language classroom.

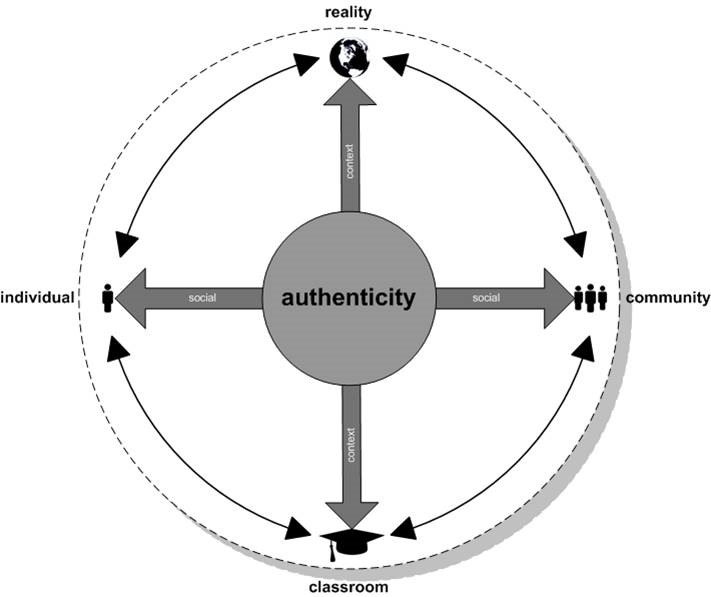

Following Breen, I created a visualisation of the domains of authenticity, mainly just because I like diagrams.

This is basically what Breen was talking about, and as one can see there is a lot of overlap and yet authenticity can relate to four very different aspects of the work we do in the language classroom. What is fundamentally important here, is that a teacher could bring in an example of a so-called ‘authentic’ text and use it in a way which is not authentic. For example, a teacher could bring an English language newspaper to class and tell her students read the text and underline every instance of the present perfect aspect or passive tense, then get them to copy each sentence out into their notebooks. Is this authentic? Although for many people the newspaper is a classic example of an authentic text, what is happening in this class is anything but authentic language learning.

Authentic materials are often defined as something not specifically designed for language learning, or “language where no concessions are made to foreign speakers” (Harmer, 2008, p. 273). In the Longman Dictionary of Applied Linguistics, the definition of authenticity is covered in a short entry, and boils down to materials “not originally developed for pedagogical purposes” (Richards & Schmidt, 2013, p. 43). Are there any problems with this definition? When I speak with other teachers, this is generally the definition they come up with, unless we are in the midst of a particularly philosophical discussion, which, don’t worry, I will come to shortly.

Henry Widdowson is one of the biggest names associated with the authenticity debate, and I had the honour of meeting him in Tokyo last year in November 2014. Widdowson made the famous distinction between materials which are authentic and materials which are genuine (1978). Basically, genuineness relates to an absolute property of the text, in other words realia or some product of the target language community like a train timetable or the aforementioned ‘classic’ newspaper. Authenticity, however, is relative to the way the learners engage with the material and their relationship to it. Hung and Victor Chen (2007, p. 149) have also discussed this, problematizing the act of taking something out of one context and bringing it into another (the classroom) expecting its function and authenticity to remain the same. They call this extrapolation techniques, which they criticise heavily for missing the wood for the trees. In other words, simply taking a newspaper out of an English speaking context quite often means you leave the real reason for interacting with it behind, which seriously impairs its authenticity. Another very big problem with this definition is that it seems to advocate the dreaded ‘native speaker’ idea, which as we all know is an emotive argument that has been discussed widely in recent years, particularly with the rise of English as a Lingua Franca and Global English. When Widdowson made his arguments it was during the rise of Communicative Language Teaching (CLT), and as part of this methodology there was an explosion in the debate around authenticity. In particular, people writing about authenticity wanted to distance the concept from the evil ‘native speaker’ definition. But what about learning aims? What about the student’s needs? How was the debate made relevant to the actual practice of teaching?

In his famous and fascinating paper, Suresh Canagarajah (1993) discusses the way students in Sri Lanka were not only ambiguous towards, but at times detached from the content of their prescribed textbooks, based on American Kernel Lessons. The students had trouble connecting the reality presented in the textbooks with their own reality, which was markedly different to say the least. Canagarajah notes that some students’ textbooks contained vulgar doodles, which he thought could perhaps have been “aimed at insulting the English instructors, or the publishers of the textbook, or the U.S. characters represented” (1993, p. 614). This connects strongly with What Leo van Lier (1996) calls authentication; the idea that learners have to make the materials authentic by engaging with it in some way on an individual level. Van Lier’s reasoning is that something can’t be authentic for everyone at the same time, but the important thing is to try and get that balance.

As I think this article has already shown, the concept of authenticity is not easy to define. Alex Gilmore, in his State-of-the-Art paper identified as many as eight inter-related definitions, which were:

- the language produced by native speakers for native speakers in a particular language community

- the language produced by a real speaker/writer for a real audience, conveying a real message (as in, not contrived but having a genuine purpose, following Morrow, 1977)

- the qualities bestowed on a text by the receiver, in that it is not seen as something already in a text itself, but is how the reader/listener perceives it)

- the interaction between students and teachers and is a “personal process of engagement” (van Lier, 1996, p. 128)

- the types of task chosen

- the social situation of the classroom

- authenticity as it relates to assessment and the Target Language Use Domain (Bachman & Palmer, 1996)

- culture, and the ability to behave or think like a target language group in order to be validated by them

Adapted from Gilmore (2007, p. 98)

In order to simplify these definitions I have developed a diagram to show how they overlap and contradict each other. I will use this diagram later as the basis for a continuum of authenticity in language learning.

Another way of thinking about authenticity is from a wider perspective, something that encompasses not only the materials being used and the tasks set to engage with them, but also the people in the classroom and the social context of the target language. To better illustrate this, I proposed that authenticity be seen as something like a continuum, with both social and contextual axes (Pinner, 2014b).

The vertical axis represents relevance to the user of the language or the individual, which in most cases will be the learner although it could also be the teacher when selecting materials. The horizontal lines represent the context in which the language is used. Using this continuum, materials, tasks and language in use can be evaluated according to relevance and context without the danger of relying on a pre-defined notion of culture or falling back into “extrapolation approaches”.

As you can see, although the word Authenticity is used all the time in staff rooms and to sell textbooks, if we actually drill down into it we get into very boggy ground.

Dogme ELT and Authenticity (and motivation)

Most readers will probably be familiar with the idea of Dogme ELT, which basically tries to get away from “the prevailing culture of mass-produced, shrink-wrapped lessons, delivered in an anodyne in-flight magazine style” (Meddings & Thornbury, 2003). This movement in ELT has strong connotations for authentic language teaching and also provides a very real connection between authenticity and motivation.

In essence, the Dogme approach places a premium on conversational interaction among teacher and learners where communication is authentic and learner-driven rather than pedagogically contrived and controlled by the teacher. Choice of learning content and materials is thus shaped by students’ own preferred interests and agendas, and language development emerges through the scaffolded dialogic interactions among learners and the teacher. Relevant to our concerns here is the value Dogme places on students’ own voices and identities in these conversational interactions. Ushioda (2011, p. 205)

In essence, Ushioda is noting that Dogme is both authentic and potentially motivating because it places the emphasis on the learners as people.

If we take a moment to see where we are with the issue of authenticity, we will realise that the definition of authenticity, although a tangle of concepts and resistant to a single definition, what it seems to be pushing at is essentially something very practical. If something is going to be authentic, it needs to be relevant to the learners and it needs to be able to help them speak in real (as in not contrived) situations. In other words, when they step out of the classroom, what they did in the classroom should have prepared them to speak and understand the target language. In order to achieve this, what they do in the classroom has to be as authentic as possible, and by implication it needs to be engaging. Essentially, authentic materials should be motivating materials.

Authenticity is a good thing. It sounds like a good thing and by association, anything labelled as inauthentic must be bad. However, I think that the word authenticity is complicit with many of the problems in English language teaching. Authenticity is still too often defined in a way which, either directly or indirectly, infers the privilege of the native speaker (Pinner, 2014a, 2014b). However, if we can get away from that, authenticity can be a powerful concept to empower both learners and teachers, because authenticity connects the individual learner to the content used for learning. So, in summary ‘keep it real’.

References

Bachman, L. F., & Palmer, A. S. (1996). Language testing in practice: Designing and developing useful language tests (Vol. 1): oxford university press.

Breen, M. P. (1985). Authenticity in the Language Classroom. Applied Linguistics, 6(1), 60-70.

Canagarajah, A. S. (1993). Critical Ethnography of a Sri Lankan Classroom: Ambiguities in Student Opposition to Reproduction Through ESOL. TESOL quarterly, 27(4), 601-626. doi: 10.2307/3587398

Gilmore, A. (2007). Authentic materials and authenticity in foreign language learning. Language Teaching, 40(02), 97-118. doi: 10.1017/S0261444807004144

Harmer, J. (2008). The practice of English language teaching (Fourth Edition ed.). London: Pearson/Longman.

Hung, D., & Victor Chen, D.-T. (2007). Context–process authenticity in learning: implications for identity enculturation and boundary crossing. Educational Technology Research and Development, 55(2), 147-167. doi: 10.1007/s11423-006-9008-3

Meddings, L., & Thornbury, S. (2003, Thursday 17 April 2003). Dogme still able to divide ELT. Retrieved 4th February, 2015, from http://www.theguardian.com/education/2003/apr/17/tefl.lukemeddings

Pinner, R. S. (2014a). The Authenticity Continuum: Empowering international voices. English Language Teacher Education and Development, 16(1), 9 – 17.

Pinner, R. S. (2014b). The authenticity continuum: Towards a definition incorporating international voices. English Today, 30(04), 22-27. doi: 10.1017/S0266078414000364

Richards, J. C., & Schmidt, R. W. (2013). Longman dictionary of language teaching and applied linguistics. Harlow: Routledge.

Ushioda, E. (2011). Language learning motivation, self and identity: current theoretical perspectives. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 24(3), 199-210. doi: 10.1080/09588221.2010.538701

van Lier, L. (1996). Interaction in the language curriculum: Awareness, autonomy and authenticity. London: Longman.

Widdowson, H. G. (1978). Teaching language as communication. Oxford: Oxford University Press.